- NASA released the first full-color images from its new James Webb Space Telescope this week.

- JWST's infrared reveals never-before-seen cosmic details, like newborn stars and ancient galaxies.

- An astronomer explains how these Easter eggs revolutionize our understanding of the universe.

NASA released the first full-color pictures from its new James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) this week.

The telescope, which launched last December, is already making discoveries in deep space. It's 100 times stronger than its predecessor, the Hubble Space Telescope. JWST's infrared cameras detect light in the far-red part of the spectrum, allowing its view to cut through dust clouds and see stars, galaxies, and other cosmic objects that were invisible to previous observatories.

"The first thing that everyone did was compare with Hubble, and you could see instantly so much more detail," Aayush Saxena, an extragalactic astronomer at University College London, told Insider.

"It was absolutely mind-boggling," he said.

Here is what JWST revealed in the four pictures released this week, according to Saxena:

Infrared cuts through dust and shows very old objects

Hubble captured groundbreaking images of deep space, but it had little ability to image in the infrared spectrum. Its instruments were mostly focused on picking up visible and ultraviolet light.

But older objects tend to let off light that is closer to the red side of the color spectrum, a phenomenon called red-shifting.

As the universe expands, galaxies are moving away from Earth very quickly. "It's kind of like an ambulance: When it's approaching us, the sound gets shriller, but then as it moves away, the sound wavelength sort of gets longer and longer," Saxena said.

In the same way, the light gets stretched and redshifted.

While visible light is absorbed by space dust that can cluster around interesting objects, blocking them from view, infrared light can cut through dust.

This is why instruments aboard JWST that can pick up infrared, like the mid- and near-infrared cameras (MIRI and NIRCam), are so valuable to science.

James Webb Space Telescope looked deep into our galaxy to see the birth of stars

JWST peered through the Milky Way to capture this image of cliff-like formations of gas and dust on the edge of the Carina Nebula, which is 7,600 light-years away from Earth.

In clouds like this, gas and dust are compressed and collapse into new stars. That's why astronomers often refer to nebulas as "stellar nurseries." JWST's infrared powers allow it to pierce through the dust and see the baby stars deep within the clouds.

"It is really cool to be able to see this, because without MIRI and NIRCam, I don't think we would be able to witness the birth of new stars," Saxena said.

Nebulas form when a massive star, or a cluster of massive stars, goes supernova, expelling their outer gas layers, Saxena said. Gravity can pull that material back together to make new stars and even fuse new elements. By spotting these stars, JWST is capturing the process that created everything in our world.

"All of the chemical elements — the carbon, the oxygen — have formed as a result of multiple generations of stars forming and dying. The first generation of stars were only made of hydrogen and helium, because those are the elements that the Big Bang gave us," Saxena said.

"We say that we are all made of star stuff, and it's kind of true," Saxena said.

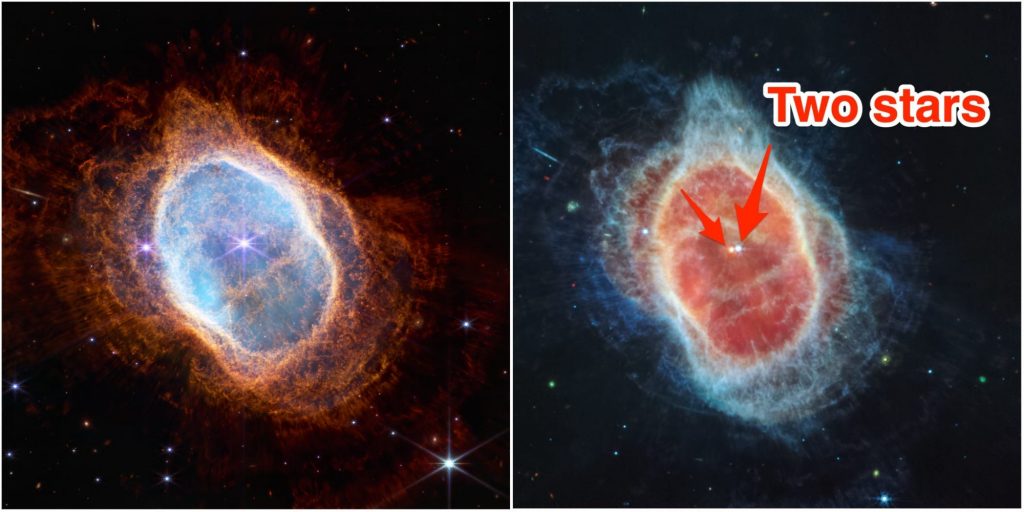

The Southern Ring Nebula's second star was only a theory before these pictures

MIRI revealed a second star at the center of the Southern Ring Nebula, about 2,000 light-years away.

"This had been theorized, but were never observed," Saxena said.

The star was outshined by its neighbor, until infrared revealed it — a red dot alongside a blue-white star. The red star is old, dying, and sending out shockwaves of gas and dust, which create the ring-like nebula around it.

The picture revealed another surprise: a galaxy in the background, which was previously not clear enough to identify, since we're looking at it from the side.

"You can see the spiral structure and a little bulge in the middle, which is a tell sign that this is actually a galaxy," Saxena said, adding, "This is only possible because of a very high resolution from these images."

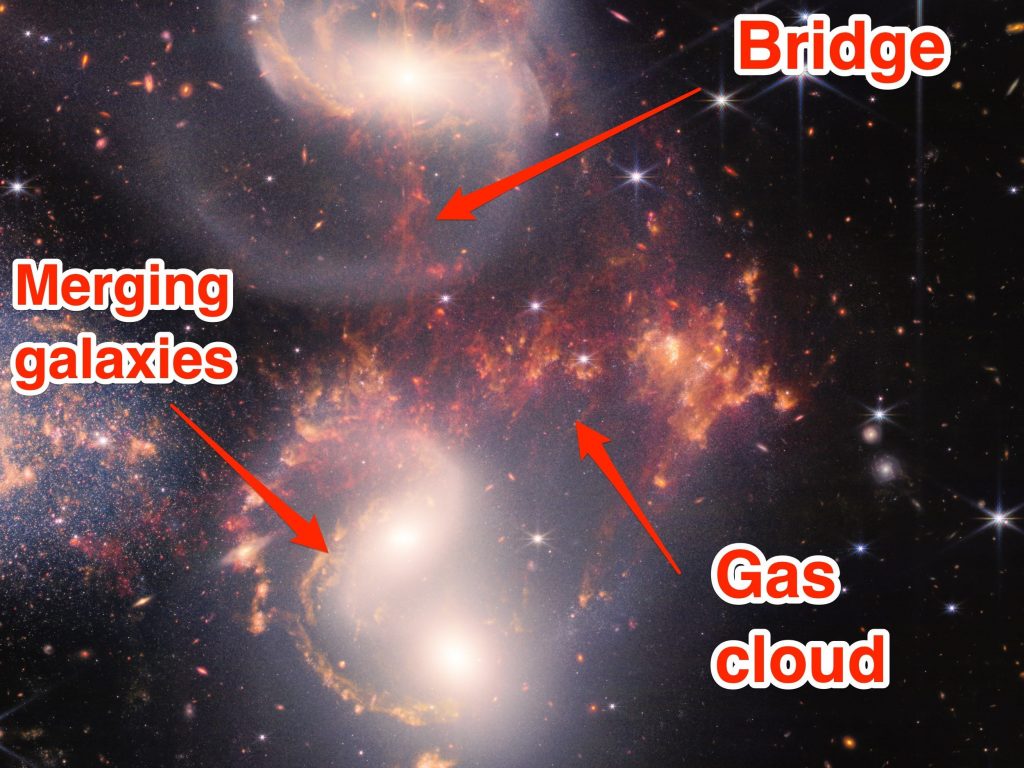

Stephan's Quintet could tell us how many stars are in a galaxy

Stephan's Quintet is a group of five galaxies, four of which are interacting with each other, 290 million light-years away. The fifth, at the bottom, is much closer, about 40 million light-years from Earth.

"You can see that the level of detail that we uncovered in infrared wavelength is so much higher compared to the ultraviolet and optical, purely because these are all possibly star-forming regions that are obscured by dust," Saxena said.

The galaxy on the left offers unprecedented insight into how stars form, he added.

"We can really pick out the individual star-forming clumps," Saxena said.

This "helps to quantify how many stars actually exist in galaxies, and how many stars are being formed within the galaxy at any given time," he added.

JWST also revealed the delicate dance between galaxies that pull on each other as they move through space. The dust and gas visible between the galaxies suggest they've come close to colliding, Saxena said.

"I think they've had a close encounter at some point in the past, which is why there's some sort of material flowing between these two, forming this bridge structure," he said.

The area between the galaxies is filled with ionized gas. When a galaxy goes through the gas, it can become very hot and ionized and emit a lot of light, said Saxena.

The gas cloud between the three galaxies is a shock front, which tells us that the galaxies are merging, Saxena said.

There are more galactic marvels throughout the background of the image of Stephan's Quintet.

"Every pixel full of galaxies, wherever you look," Saxena said, adding, "You can really see the beautiful spiral arms and the bulge and everything."

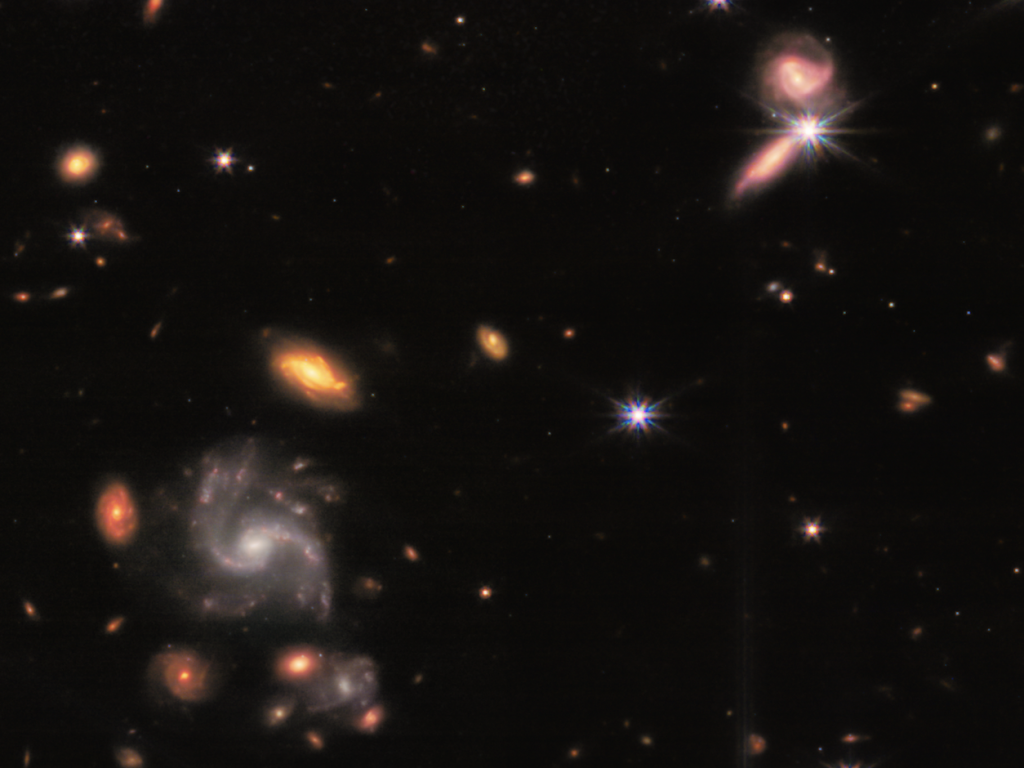

JWST's deep field image reveals one of the oldest galaxies ever observed

JWST also turned its attention to a cluster of galaxies about 4.24 billion light-years away, called SMACS 0723.

This cluster allows us to see galaxies that are much farther away, through an effect called gravitational lensing.

"It's kind of like looking through a wine glass. If you see something through the bottom of the wine glass, it appears ring-like and stretched, which is called lensing," Saxena said, adding, "Following Einstein's general theory of relativity, if there's a massive object between us and a background object, the light from the background object bends around it and stretches."

The gravitational pull from the cluster of galaxies is so strong that it mirrors and stretches light from galaxies far behind it, as seen in the image below.

For Saxena, it's the tiny red dots in the picture, rather than the galaxies, that are most interesting.

The farther away a galaxy is, the redder and more compact its light will be. NASA determined that this red dot is 13.1 billion years old, one of the oldest galaxies ever spotted.

"Once you bump up the contrast, I'm sure more and more such red dots will appear. Inevitably, one of them might just turn out to be one of the most distant galaxies that you might end up finding," said Saxena.